Here we have a movie that comes from Edgar Wright, a director known for light horror movies that spoof the genre while obviously enjoying it. Last Night in Soho doesn’t spoof as much as revel, and while it clearly establishes a unique perspective on a narrative that has all but died in horror/mystery movies, its second half completely implodes as it goes off the rails, until Diana Rigg finally emerges from the shadows where she’s been lurking to deliver her final performance and reel in the mess and bring it back home into a cohesive but messy close.

The movie introduces us to Ellie (Thomasin McKenzie), a fashion designer wannabe obsessed with the 60s who gets accepted to go to London to study her passion. Her grandmother (Rita Tushingham) warns Ellie about the city, mainly because she fears Ellie’s talent for seeing spirits may take over her as it did her mother, who has since died tragically. However, Ellie promises she can fend for herself, and before we know it, she’s off to London where she meets a bitchy roommate (Synnove Karlsen) and a potential love interest (Michael Ajao).

When her living conditions prove to be incompatible she answers an ad for a room for rent. The landlady who runs the townhome is Ms. Collins (Diana Rigg), another grandmotherly type who lays down the law. Ellie, still wide-eyed about London, assures Ms. Collins she will have no trouble being a tenant. However, that night, as she goes to sleep, she wakes up in the middle of 1960s Swinging London and has inexplicably walked into someone else’s reality and is merely a spectator.

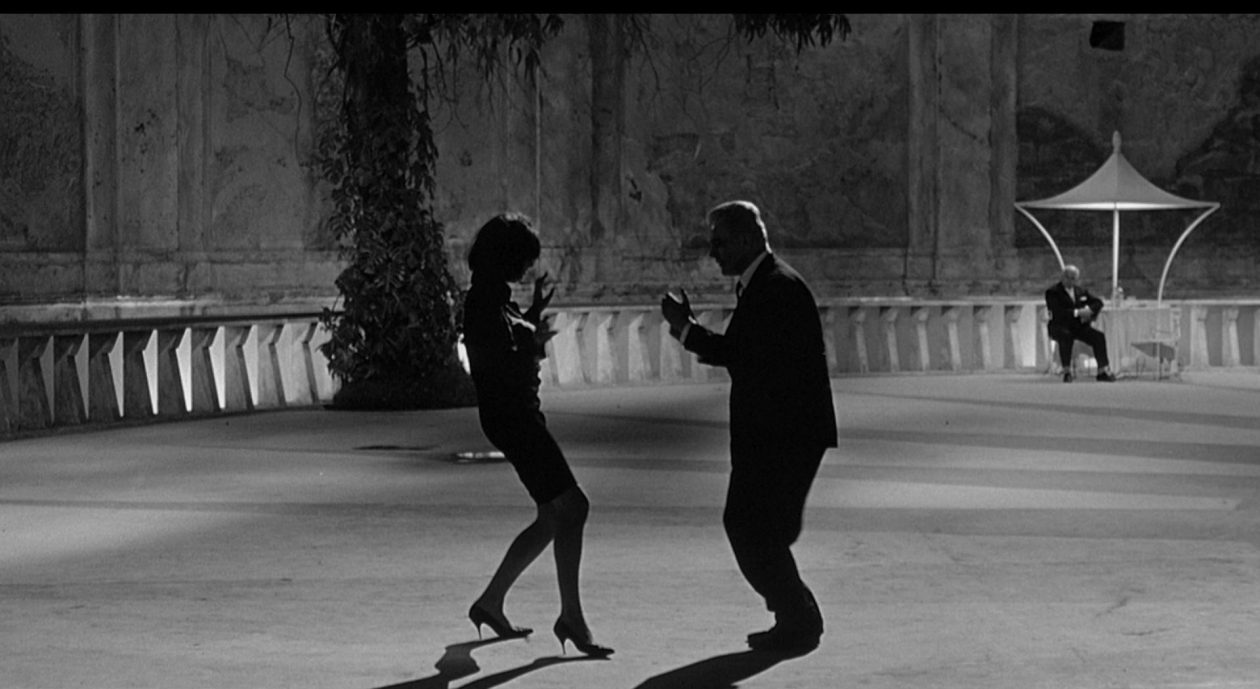

That someone turns out to be Sandie (Anna Taylor-Joy). Sandie struts around London with an exuberance and self-assured confidence that would make Holly Golightly take note. However, with such females, bell that surface is a young woman longing to make her mark on the world as a singer. Sandie wanders and latches onto the Rialto, a nightclub where singers like Cilla Clark perform. She meets Jack (Matt Smith), a dashing but slightly older man, who sees potential and gives her a spot. If only Sandie would know what awaits her, she would have turned tail and run away.

Here is where the movie shines the best. It moves effortlessly from the past to the present, and often blurs the lines between the two. In including Ellie in what seems to be a mirror world of Sandie’s, Wright tells delivers a clever little piece about time folding in on itself, and that’s not an easy trick to achieve. Through Ellie, we get a look into Sandie’s life and this begins to affect Ellie in her own life. Off comes Ellie’s mousy brown color and retro 90s look, and Ellie transforms herself into a blond with a penchant for cooler outfits. The change starts to inform Ellie’s fashion sense, which also catches the eye of her teacher who sees great potential.

But this is a mystery after all, and Ellie’s school designs take a back seat to the meatier story about to unfold. Every time Ellie wakes up as Sandie, she witnesses how the initial shimmer and glamor starts to reveal the cracks in its surface. Soon it becomes clear that Sandie has walked into a trap of human trafficking and is in some form of imminent danger from Jack and the men she is forced to sleep with to pay her dues. [And with this, Last Night in Soho also delivers its social message to the public.]

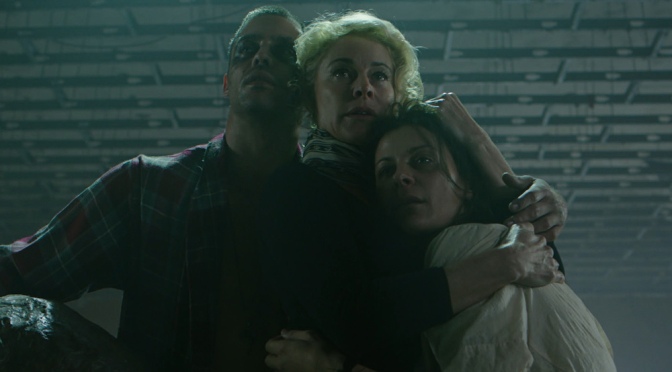

Meanwhile, Ellie starts to lose her grip and devolve into something else. Like all horror-movie conduits, Ellie becomes obsessed with somehow breaking the invisible glass that separates her from Sandie and possibly changing Sandie’s destiny. One particularly horrific vision informs Ellie that Sandie met a horrible fate. Trying to get to the core of the mystery (and possibly rectify it) she crosses the path of an old man (Terence Stamp) who may know more than what he is willing to disclose. And what of the men who went missing in Sandie’s neighborhood during the years after Sandie’s horrific murder?

I’m a bit torn with this movie. For a horror movie lover who also loves a good mystery and parallel times, this one is a crowd pleaser that will deliver on all aspects. Last Night in Soho‘s first 30 minutes are truly glorious — restrained and greyish where it needs to be, because we’re in Ellie’s rather sheltered reality. Once it ventures into the 60s, the movie explodes in color reminiscent of Technicolor and that soundtrack is a killer. Anna Taylor-Joy emerges as a pure creation of the era, with her hair and dresses. You truly believe she was one of the many carefree girls parading through London and possibly catching David Hemming’s misogynistic eye as Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills did in Blow Up.

The main issue that I had with Last Night in Soho is the fact that this being a mystery with horror elements, it never quite knows what to do with the horror aspect. Wright relies too much on apparitions and these detracted from the entire movie if not outright ruined it for me. The movie has a Broadway feel to it, where everything has to be telegraphed to the farthest seat in the house with loud, garish brush strokes and Giallo imagery. Then the movie takes a hard left turn, and while it is surprising, it also doesn’t entirely convince. At best, it looks tacked on, but then, many horror movies have tacked-on endings, so who am I to judge?

Thomasin McKensie is a solid actress, but the script has her come apart at the seams. She starts the movie so natural and self-confident, but by the end she’s been reduced to talking in whispers and barely even there. It just didn’t work for me. I wish that her character would have been less a Shelly Duvall and more a heroine. That kind of simpering, horror novel female has not been seen since the 60s, although perhaps, because Ellie is so obsessed with this decade, she actually filters women’s behavior of the time.

Anna Taylor-Joy has the stronger part of the two despite her co-starring screen time. Whenever she enters the movie, it takes on an entirely different dimension, and her character arc is tragic right up until the “What happened to her, really?” moment. As a plus, the movie gives many icons of the era in their twilight performances — Diana Rigg and Terence Stamp, for one. Margaret Nolan, a Bond girl of the time, shows up as a bartender. All throw in some much needed

class into this movie. Other than that, this is candy-colored horror with a strong Signet Paperback feel to it, and that, while not a bad thing, is also, not a good thing.